For every project, you have one chance to set the tone for how painful it will be to work on the project as it grows. The reason we don’t see issues until it’s too late is that almost any structure works when the project is small enough. Making decisions that make a project more maintainable comes with many benefits for yourself and your team.

- Evolving requirements: Over time, business requirements may change, new features are added, and old features might become obsolete. A maintainable project can adapt to these changes more efficiently.

- Easier debugging: When a project is maintainable, it's easier to understand the flow of data and logic, making it quicker and simpler to identify and fix bugs.

- Scalability: As your project grows, you want to ensure it can scale without significant performance issues. A maintainable codebase allows better scalability by organizing the project architecture in a way that can handle increased load.

In short, investing in maintainability can save a lot of time, effort, and resources in the long run.

There are 2 prominent approaches that you’ll encounter in the frontend world:

- Type-first structure: involves grouping files based on their type: components, hooks, utils, routes, and the like.

src/

├── components/

│ ├── Button.tsx

│ ├── Card.tsx

│ └── Input.tsx

├── pages/

│ ├── Home.tsx

│ ├── About.tsx

│ └── Contact.tsx

├── hooks/

│ ├── useAuth.ts

│ └── useForm.ts

├── styles/

│ ├── global.css

│ └── variables.css

├── utils/

│ └── helpers.ts

└── constants/

└── config.ts

- Feature-based structure: involves grouping files based on a common domain.

src/

├── features/

│ ├── auth/

│ │ ├── components/

│ │ ├── composables/

│ │ └── utils/

│ ├── products/

│ │ ├── components/

│ │ ├── composables/

│ │ └── utils/

│ └── checkout/

│ ├── components/

│ ├── composables/

│ └── utils/

├── components/

├── composables/

├── layouts/

├── pages/

├── public/

└── server/

Both structures are not mutually exclusive. Usually, one takes the primary role. For the type-first structure, when used in a sizable project, you end up needing to group components that share a common domain into folders. You end up with feature folders nested in each type folder.

src/

├── components/

│ ├── auth/

│ │ ├── LoginButton.tsx

│ │ └── SignupForm.tsx

│ ├── products/

│ │ ├── ProductCard.tsx

│ │ └── ProductList.tsx

│ └── shared/

│ ├── Button.tsx

│ ├── Card.tsx

│ └── Input.tsx

├── pages/

│ ├── auth/

│ │ ├── login.tsx

│ │ └── signup.tsx

│ ├── products/

│ │ ├── index.tsx

│ │ └── [id].tsx

│ └── index.tsx

├── hooks/

│ ├── auth/

│ │ ├── useAuth.ts

│ │ └── usePermissions.ts

│ ├── products/

│ │ ├── useProduct.ts

│ │ └── useProductList.ts

│ └── shared/

│ └── useForm.ts

├── styles/

│ ├── global.css

│ └── variables.css

├── utils/

└── constants/

├── auth/

│ └── authConfig.ts

├── products/

│ └── productConfig.ts

└── shared/

└── config.ts

What are some of the downsides when going this route?

-

Increase mental load: This approach introduces cognitive load for any developer (including yourself) who needs to understand code for a specific feature either to fix a bug or to extend it.

-

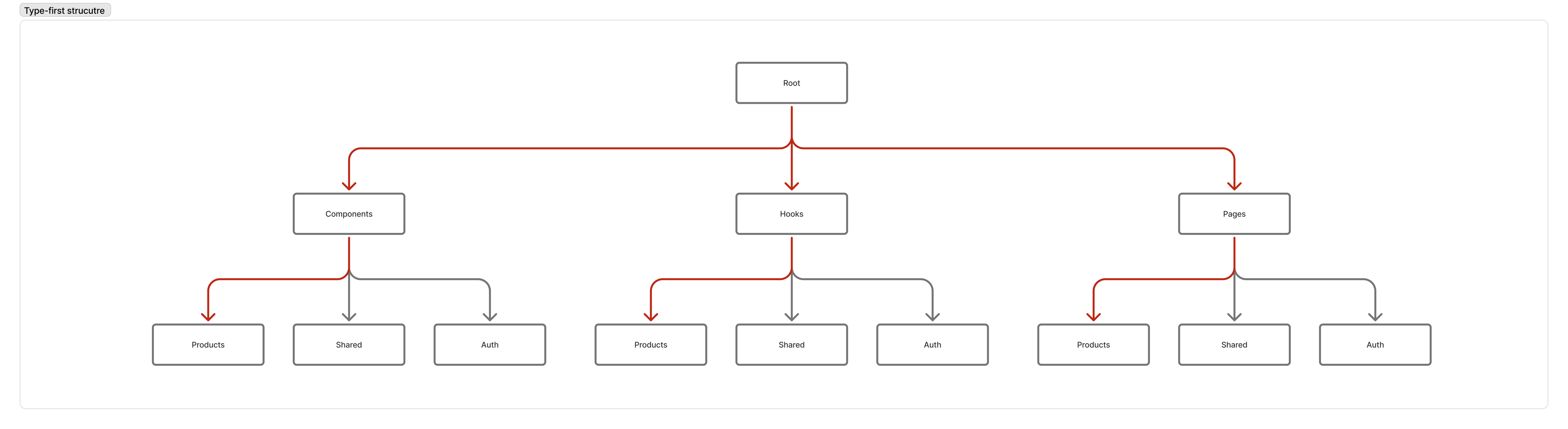

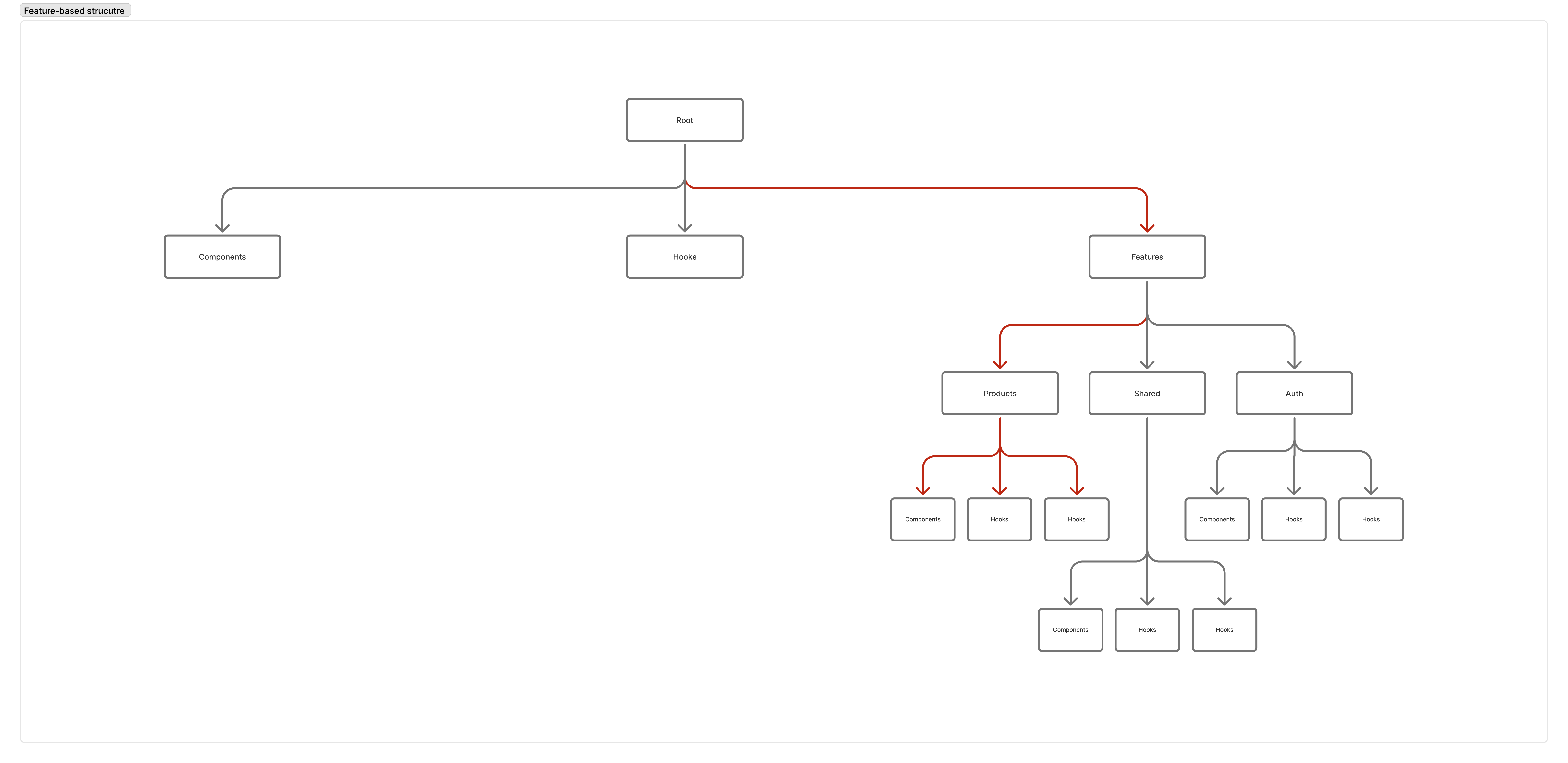

Increased visual clutter: Compare the following illustrations. Assuming you have a project with two features: product and auth. The red flow lines show the folders you ideally want to have expanded as a new dev trying to understand the product feature.

From the illustrations you can see as the number of features grows it will be increasingly painful to traverse code related to one specific feature.

The feature-based approach works well beyond frontend development. From experience, it is also useful when setting up Node.js backend applications.